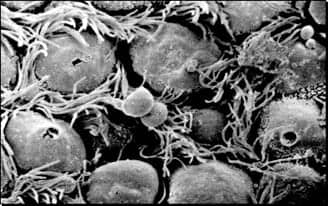

New research identifies a new technique that can aid clinicians in making earlier, more accurate diagnoses of ciliary dyskinesia, a condition that can mimic the symptoms of less serious diseases. Shannon Quinn, lead author of the study, says, “The disorder causes the cilia to not move properly. Without the proper motion, they can’t clear out mucus and with that you get anything from flu-like symptoms, all the way up to lung scarring necessitating lung transplants.”

According to a University of Georgia (UGA) news report, clinicians go through a series of steps to diagnose ciliary dyskinesia, with the final step involving analyzing motions with video microscopy. From the videos, clinicians or researchers make a determination about whether or not the motion is normal.

Quinn explains, “It’s that last step that we’re focusing on. Researchers or clinicians making this determination based on their own training and experience is the current state of the art, but it is subjective, laborious and error prone. There is no cross-institutional commonality for making the diagnoses.” Quinn adds, “So our goal was to provide a quantitative baseline for that particular step in the diagnostic process.”

The UGA news report notes that by providing a baseline for this one step in the diagnostic process for ciliary dyskinesia, the researchers have established a pipeline to take some of the guesswork out of the process. According to Quinn, “To be able to attach numbers to the motion introduces a higher degree of certainty in diagnosing the abnormalities. It provides a quantitative definition that is relevant across clinics, across research institutions, and it’s all automated so that we have a direct comparison between motion types.”

This faster diagnosis is applicable across the class of disorders that involve cilia dyskinesia. A growing body of research on cilia suggests a variety of other conditions could be implicated by the disorder, as noted on the UGA news report. Quinn states, “Identifying these abnormalities more rigorously and earlier could help limit the need for more invasive procedures later on.”

Source: University of Georgia