A recent study reveals a vital role of monocytes in the immune system changes that occur with age, which may help explain why older adults are more susceptible to pneumonia.

Comparing younger and older mice, the researchers found that the latter have higher numbers of monocytes both in the bone marrow and in the blood. They also saw higher levels of TNF and IL-6, two pro-inflammatory cytokines, in blood from older mice and blood from older human donors. Studying mouse monocytes in more detail, the researchers found that the increase in TNF levels that occurs with age causes premature release of immature monocytes from the bone marrow into the blood stream. When stimulated with bacterial products, these immature monocytes themselves produce more inflammatory cytokines, thus further increasing levels in the blood.

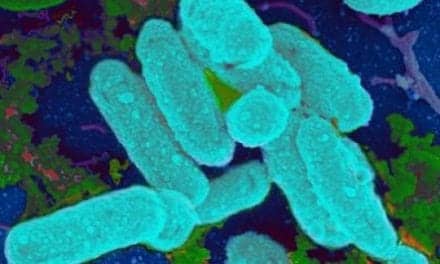

The researchers then infected younger and older mice with the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae, which causes so-called pneumococcal pneumonia. They found that, although the older mice had higher numbers of monocytes in the blood and at the sites of infection, their monocytes were not able to clear the bacteria and successfully fight the infection. However, when the researchers used drugs or mouse mutations that reduced the number of monocytes or removed TNF, they were able to restore antibacterial immunity in aged mice.

The researchers conclude that “monocytes both contribute to age-associated inflammation and are impaired by chronic exposure to the inflammatory cytokine TNF, which ultimately impairs their anti-pneumococcal function.” They go on to suggest that “lowering levels of TNF may be an effective strategy in improving host defense against S. pneumoniae in older adults,” and that, “although it may be counterintuitive to limit inflammatory responses during a bacterial infection, [some existing] clinical observations and our animal model indicate that anti-bacterial strategies need to be tailored to the age of the host.”