Researchers at Stanford University are developing a new vaccine that could potentially provide multi-strain and multi-season innoculation against the influenza virus.

By Mike Fratantoro

Every year, tens of thousands of Americans contract the flu. While the majority of those afflicted recover normally, a number of patients die as a result of the virus. Flu-related illnesses can kill 3,000 to 49,000 Americans annually, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (The imprecise range is due to a number of factors, according to the CDC, including nonconsistent reporting and the frequency of other diseases and conditions that contribute to the cause of death.)

Much of the problem in preventing the illness comes from the fact that the influenza virus is ever-evolving, with a new strain emerging each season. This means scientists must create new vaccines every year, tailored specifically for the new strains.

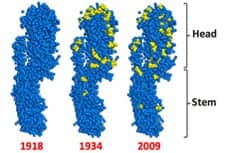

This image shows the hemagglutinin (HA) protein—the target for current influenza vaccines—from three flu strains. The blue and yellow dots depict the amino acids that make up the HA protein. The yellow dots show amino acids that change in the 1934 and 2009 protein, relative to the 1918 variant. Current vaccines are created using the head of the virus, where more changes occur. But a new flu vaccine based on the stem of the HA protein is being developed by Stanford researchers, which could yield a vaccine that protects against different strains of flu, and perhaps for more than 1 year at a time. (Credit: Stanford University)

But researchers at Stanford University are homing in on a new vaccine that could be produced more quickly and offer broader protection than the virus-specific inoculations available today, according to results they have published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Their “universal” flu vaccine may protect against multiple influenza strains and potentially last longer than one season, according to the research team, which based their work on the structure of the hemagglutinin (HA) proteins found within the flu virus.

Each HA protein includes a stem and a head section, the latter of which is used as the basis for current flu vaccines. Researchers explain that the head of the HA protein varies year to year, whereas the stem remains more constant over time. Based on its relative stability, Stanford team’s new vaccine targets the stem, which they say could offer multi-season protection once the immune system produces the necessary antibodies.

The Stanford method remains experimental and has not yet been tested on patients, but researchers are working to create a protein stem fragment that could be injected into the bloodstream. This would create a target (or antigen) for the immune system and trigger an effective defense, the researchers explain.

The entire process is outlined in the PNAS article, but over the course of 2 years researchers used DNA sequencing and an experimental process called cell free protein synthesis (CFPS) to create and refine a soluble viral protein stem that would be useful as an experimental vaccine antigen. Their next steps include attaching this stem protein to a virus-like particle to create a better target for immune system response, and then, if successful, safety and efficacy tests in animals and, eventually, large scale human clinical trials.

“This is an important project for world health,” said lead researcher James R. Swartz of the Stanford University School of Engineering, in a released statement. “These are big challenges but we are committed to the effort.”

Though by no means a cure for the influenza virus, the multi-strain, multi-season vaccine would do much to reduce the tens of thousands of American deaths and the 250,000 to 500,000 people worldwide who die each year from flu-related illnesses, according to the World Health Organization. RT

Mike Fratantoro is the chief editor for RT Magazine. For more information contact [email protected].