Courtesy: Lehigh Valley Health Network, Pennsylvania

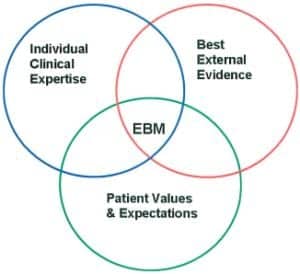

As a manager in a large teaching hospital, I introduce new procedures and equipment on a monthly basis to provide the most advanced care to our patients. As I proceed in my health care informatics course, I am learning how information technology bridges all the components of my job: biomedical engineering, computer applications, and creating and managing health policies. This can be accomplished by utilizing evidence-based medicine (EBM), which is an explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the patient.1 The purpose of this paper is to examine how EBM improves quality and to offer recommendations on how to develop best practices for your area of health care.

The Role of Health Informatics

Evidence-based medicine is driven by health informatics, a discipline at the intersection of information science, computer science, and health care. It deals with the resources, devices, and methods required to optimize the acquisition, storage, retrieval, and use of information in health and biomedicine.2 Before starting this course, I assumed health informatics was more computer science-driven with less emphasis on medical evidence, but I soon learned that health informatics includes not only computers but also clinical guidelines, formal medical terminologies, and information and communication systems.2 We need to understand how health informatics influences and supports our decisions when setting policies for clinical care.

Using the Evidence

Working in critical care involves processing information, treating our patients, and documenting our actions at the bedside, and when creating best practices, we need to read the medical literature that is available and then interpret and apply it to our patients.

Utilizing EBM is not new to the medical world. John Graunt (1620-1674) used this method in London, to estimate a relationship among live-born children who died before the age of 6 by utilizing medical assignments to track health and social conditions.1 Hospitals, especially teaching hospitals, took an interest and integrated clinical experts and best practices for patient care based on evidence. This is of great interest to me because the hospital where I work has seven different intensive care units with at least 10 different physicians practicing in each area of specialty. A clinician such as a nurse, respiratory therapist, pharmacist, or intern could easily get confused, as the physicians change service weekly. Now, clinicians can make decisions based on research rather than on how they had been practicing in the past, with little science to back up their decisions. By utilizing a group of clinicians, EBM can be a great learning tool and can build and produce teamwork and camaraderie with fellow clinicians.

Establishing Evidence-Based Medicine

So what options do we have to establish EBM, and how do we utilize health informatics to accomplish setting best practices? Clinicians can retain only so much information, and sometimes it is hard to remember all that we are required to learn on a daily basis.

We must learn to assess and find the best research that is available to make sound decisions. Evidence-based medicine can help clinicians retrieve information and extract detailed information for a specific population of patients and, thus, advance patient care.

For example, we see patients in critical care units receiving expensive drug therapies as a rescue at the end of their lives. Often this is considered off-label usage, so the insurance companies do not approve it for this type of care, which leads to the denial of payment.

Before choosing such therapy, managers first should do a literature search for this selected population of patients. Next they should look at treatments and results—specifically, how mortality rates changed while these therapies were being utilized. They might find detailed articles and case studies describing lack of evidence that this drug provided any change in mortality rates. Basically, patients would die whether they received the medication or another less expensive therapy.

My experience has taught me that EBM is an important step in problem solving and working through issues to provide increased quality through best practice.

Testing the Evidence

Hospitals today have computer access everywhere, including right at the bedside, and we can access case studies and current articles on almost anything we see and do in critical care. Unfortunately, there is a lot of unreliable literature as well, so we need to make sure the sources are reliable. Although it is difficult, it is important to evaluate the sources and make sure we compare facilities and patients that we are treating so we have similar positive results. Researching the literature can have consequences if the evidence is found to be unreliable. There are widespread databases today with copious amounts of data so we must remember to ask questions, find data that is based on relevant patient populations, and make sure the facilities that are producing the articles are reputable organizations.

There are four steps to take in providing EBM3:

- Compose a clear clinical question about a patient’s problem;

- Search through the literature for all relevant clinical articles and case studies;

- Examine the evidence and make sure it is valid;

- Extract the useful findings and apply to clinical practices.

There are some important questions clinicians need to ask when determining if the evidence is valid:

- Was the study a randomized controlled trial? This is especially important since studies could be misleading if physicians were able to assign patients to certain treatment protocols based on their treatment preference. I have seen this when physicians and staff members predetermine that a certain drug will be more efficacious than another without any evidence to back up their choices.

For this reason, it is important that clinicians and decision makers are blinded to the treatments during the trials. We were doing a liquid ventilation trial on sick infants years ago, and everyone wanted their patients to go on the blinded drug as opposed to the control drug, which was a placebo, because they knew that the trial drug was superior. It was a challenge to actually keep the study blinded.

Before relying on study findings to be valid, clinicians need to ask other crucial questions:

- How large was the patient population? One does not want to base a new clinical guideline on 10 patients, so large sample sizes are always best when choosing studies.

- How will the results help me take better care of my patients? Is this an improvement from how we are caring for our patients currently?

- Do the results apply for all patient populations or just a selected group? What happens if other areas of the hospital hear about what you are doing and want to try it on their patients? It may not be safe. (We utilize a drug for critical infants and cardiac patients, and if it is used incorrectly outside of that population, the patients could go into heart failure.)

- Is the benefit worth the potential harm and costs? Ethically, it is important to make sure that the benefits are worth the potential harms and extra costs that may be incurred.

Once these questions have been answered, clinicians should be ready to implement the drugs or therapies for the patients or develop and create hospital guidelines for hospital approval.

Just recently, my department developed guidelines for treating infants with respiratory distress syndrome based on the American Association for Respiratory Care recommendations. When the Joint Commission investigators came to survey the intensive care nursery, they asked how we created our policies and procedures. When I spoke of creating guidelines based on EBM and reviewed our protocols with them, they complimented us on utilizing literature-based evidence.

Eight years ago, hospitals faced difficulty in treating patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). This complicated disease manifests in critical patients who develop sick lungs, usually secondary to being on a ventilator. Once this occurs, the patient cannot oxygenate and we tend to beat up the lungs, which further complicates the patient’s condition. Many patients expire or end up having a tracheotomy just to wean off the ventilator.

There were many opinions on how to treat these patients, so the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded a study throughout the United States to develop treatment guidelines based on evidence. It was named the ARDSNet study,4 and the goal was to improve quality and decrease costs. Patients were randomized to either high tidal volumes or low tidal volumes to ventilate the lungs, and physicians were blinded to which protocol they were assigned until after they enrolled their patients in the study.

Eight years later, hospitals are still ventilating patients based on the results of the ARDSNet study, although it was difficult for physicians to lose their autonomy at first, since the guidelines may not have been consistent with the treatment strategies they were accustomed to applying when treating patients with ARDS.

The Benefits of EBM

There are many advantages to providing EBM in health care, and I am a proponent of this since I work at a 1,000+ bed facility with many clinicians with varied expertise and backgrounds. First, EBM integrates medical education with clinical practice and is an excellent way to educate clinicians such as doctors, nurses, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, case managers, and, especially, medical students. It is also an excellent tool to utilize during patient rounds to create a care plan for caregivers to follow to move the patient through the system as fast as possible, while providing clinically proven care.

It is possible that 30% of the total annual United States expenditure on health care is spent on ineffective procedures that are not based on evidence.5 When we hear the President talking about expanding health care, it makes us wonder if we are ready to expand something that needs to be fixed first.

Although I am a supporter of EBM, it is important that I point out some caveats to make sure we are making objective decisions. Evidence-based medicine and establishing best practices for clinical pathways are timely if you do it correctly. One needs to take the time to answer the questions properly to make good sound decisions. We sometimes have little time to do our work properly, and, when we work with the sickest patients, time is not always on our side. We need to allow group meetings to discuss at length the impact of our actions.

Another big concern is the cost of computers and updated/upgraded software. Where do the funds come from, since capital dollars have dried up completely in some facilities? My computer at work is so old that I cannot open up certain programs—and I am a director of a large department. My peers will tell you that this is not uncommon in health care today. When we discuss costs of computers and software, we can forget that access is poor in many facilities, and clinicians may not be able to look at current literature as easily as we would expect in 2011. When I went to our medical intensive care unit to count the number of computers that would be available for literature searches, there was one computer for every three clinicians, but the Internet was blocked to protect against non-work-related activity.

Conclusion

This topic is important to me, and writing this article was a valuable opportunity to research best practices to improve quality while considering the cost of providing care to critical patients. Clinicians learn a lot from the challenges they face daily, but we cannot expect everyone to retain and recall everything they learn; we must utilize EBM to create pathways and protocols to ensure that the treatment of our patients is advantageous for them and the clinicians who are caring for them. During recent surveys, The Joint Commission investigators and the Department of Health were satisfied when they saw our policies were based on evidence and that clinicians were following these procedures throughout the institution.

Raymond Malloy, MHA, RRT, is director of pulmonary care, Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals, Philadelphia. For further information, conact [email protected].

References

- Shaneyfelt T, Baum KD, Bell D, et al. Instruments for evaluating education in evidence-based practice. JAMA. 2006;296:1116-27.

- Health Informatics. Available at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_informatics. Accessed December 16, 2011.

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71-2.

- Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301-8.

- Bakken S. An informatics infrastructure is essential for evidence-based practice. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2001;8:199-201.