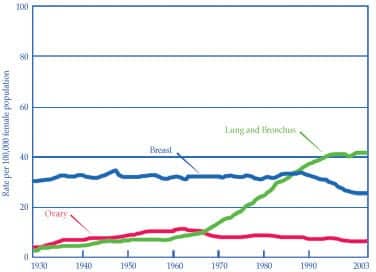

We hear a lot these days about health issues and fighting disease—particularly cancer. Cancer is often the target of advertising campaigns and fund-raising efforts. For women, breast, ovarian, and colon cancer are constantly in the spotlight. Across the nation, magazine racks at bookstores and supermarkets, television ads, and billboards call for action in fighting these three cancers. The real problematic type of cancer in women really isn’t breast, ovarian, or colon, however. It is, without a doubt, lung cancer. More women were estimated to die from lung cancer (73,000 female deaths in 2005) than from the other three most common cancers (breast, colorectal, and ovarian) combined. From estimated statistics, 27% of all cancer deaths in US women occur from lung cancer, compared to 15% of female deaths due to breast cancer and 6% due to ovarian cancer.1 The figure2 shows the age-adjusted cancer death rates in females from 1930 to 2003, and it indicates a very clear trend: Lung cancer deaths in women began climbing around the mid 1960s and have reached the number-one spot over the last 40 years. This article will review lung cancer in women and discuss the reasons this disease has a particular twist when it comes to gender.

Age-adjusted Cancer Death Rates from Lung and Bronchus, Breast, and Ovary, Females by Site, US 1930-2003

*Per 100,000, age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard pupulation Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2006.

Risk Factors, Types, Diagnosis, and Survival Rates

Since the late 1960s, cigarette marketing plans and commercials have been aimed at women. “You’ve come a long way, baby” was introduced with the new Virginia Slims cigarette to entice women to smoke their own brand of “feminine/feminist” cigarettes and thus declare their new status in society.3 Smoking has clearly been tied to cancer as a major risk factor,1 however, and 85% to 90% of individuals diagnosed with lung cancer are smokers (or former smokers).4 Other risk factors for lung cancer include second-hand smoke, age, gender, genetics, diet, infection with human papilloma virus, environmental or occupational exposure to certain agents (including radon, radiation, diesel exhaust, nickel, and silica) and exposure to asbestos (linked to mesothelioma, a cancer in the linings of the lungs, heart, and/or abdomen).4-6 Although smoking is considered risky behavior, only a minority of smokers develop lung cancer, and 10% to 15% of lung cancer cases involve nonsmokers.1

Lung cancer is divided into two main categories: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). NSCLC accounts for 75% to 80% of the diagnosis and has three subdivisions: adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell undifferentiated carcinoma. SCLC (sometimes referred to as oat cell) accounts for approximately 15% to 20% of the cases.5 For women, adenocarcinoma is the most frequent lung cancer diagnosis.

Diagnosis of lung cancer often comes late in the disease because patients frequently are asymptomatic during the early stages (approximately 90% of new cases have no symptoms). If present, the symptoms most often include cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and hemoptysis. Less often, symptoms can include anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, and hoarseness. Unfortunately, smokers often have symptoms similar to those of COPD, and the diagnosis of cancer may be delayed due to the overlap of many of these health-related issues. Cancer often shows up in a chest x-ray taken to investigate some other possible diagnosis. When a lesion has been found, bronchoscopy with transbronchial needle aspiration is often used to identify the type of cancer. Laser-induced fluorescence emission can be used to identify cancer in the airways. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging may be used to look for metastatic disease.7 Sputum cytology has been useful in screening and identifying lung cancer. Also, when a pleural effusion is present, thoracentesis is performed to drain the pleural fluid and have a sample sent for analysis—often cancer causes an effusion to form and the type of cancer can be identified by the lab.5,8

Only approximately 18% of the cases are found while the cancer is in the primary site of the lung only (this is called localized disease); 38% of the cases are diagnosed after the cancer has spread to lymph nodes in the lung or other areas of the lung structure (called regional disease), and 37% of the cases are diagnosed as metastatic disease wherein the cancer cells have spread to other parts of the body. As the cancer diagnosis changes from localized to regional to metastatic disease, associated 5-year survival rates for men and women drop from 51.3% to 17.1% to 2.1%, but in all cases, women have a better survival rate than men. When looking at all stages of disease (local, regional, and metastatic), the 5-year survival rates with NSCLC are 14.9% for men and 19.6% for women. In addition, looking at all stages of disease, the 5-year survival rates with SCLC are 5.6% for men and 7.2% for women.1

Staging and Treatment Options

Non-small cell lung cancer is classified by stages, and each stage has subsets according to size, lymph node involvement, and whether it has spread (metastasis). Stage 0 is cancer that is found only in the inner lining of cells in the airways. This stage generally reflects the earliest finding of cancer, and, since cancer is rarely found this early, it is rare. The next level is stage IA and describes a tumor less than 3 cm. Stage IB involves a tumor that has not spread to the lymph nodes and has one or more distinguishing characteristics (larger than 3 cm, involves a main bronchus, has spread into other lung tissues, may partially—but not fully—block an airway). Stage IIA tumors are smaller than 3 cm but have spread to the lymph nodes. They are not in the main bronchi and are not in other lung tissues. Stage IIB is larger than 3 cm, involves the main bronchi, and has spread to both surrounding tissues and lymph nodes, or the tumor has: a) spread to the chest wall, diaphragm, pleura, or pericardium; b) involves the main bronchi and the trachea; or c) is causing a lung to collapse or develop pneumonia, but has not spread to lymph nodes. In stage IIIA, the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes in the mediastinum or trachea on the same side as the cancerous lung. Stage IIIB cancer can be found in the bronchus, trachea, esophagus, spine, or pleural fluid but has also spread to lymph nodes on the opposite side of the chest. Finally, stage IV describes lung cancer that has metastasized to other parts of the body and involves the bones or organs such as the brain or liver. This is the most advanced stage and is essentially incurable.5,7

Within the stages, the cancer will have the letter T and a number (such as T1 or T2), which refer to the tumor size; the letter N plus a number to describe lymph node involvement; and the letter M plus a number to describe metastasis. So, for example, a patient with lung cancer might be described as having stage IIB and T2N1M0.7

Treatment for NSCLC varies with both the stages and TNM classifications, and treatment options include the “big three”: surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy—as well as immunotherapy, brachytherapy, and gene therapy. Surgery involves performing a wedge resection: removal of a lung segment; a lobectomy: removal of an entire lobe; or pneumonectomy: removal of the entire lung. SCLC involves more aggressive tumors, and without treatment, survival is very limited (untreated patients live only from around 5 to 12 weeks).7 Surgery is rarely used in the treatment of SCLC (except in the case of a SCLC involving a solitary pulmonary nodule where complete resection has increased survival to 50% at 5 years).7

Respiratory therapy procedures such as bronchodilator therapy, oxygen therapy, and bronchial hygiene therapy are used to help relieve symptoms in lung cancer patients. Adequate nutritional support is also very important to these patients in order to maintain the body’s health and strength. Malnourishment and dehydration are often problems for cancer patients due to the side effects of radiation and chemotherapy, which include nausea, vomiting, mouth and GI tract sores, and loss of appetite.5

Implications for Women

Although smoking has decreased since hitting a peak in the 1960s, the decrease in men has been more dramatic (prevalence in men has decreased by one half) compared to the decrease in women (prevalence in women has decreased only by one quarter). Once women have begun smoking, they appear to be less successful in quitting compared to men.9 When considering cases of lung cancer in nonsmokers, approximately three times more cases occur in women compared to men.1 Looking at physiology, in comparison to men, women have a higher percentage of body fat; higher levels of estrogen and progestin; and lower muscle mass, blood pressure, and levels of androgen. Women also have fluctuations in hormone levels related to monthly ovulation cycles and pregnancy. Moreover, they have changes related to menopause in organs such as the ovaries, breast, uterus, brain, and skin, and cardiovascular tissue and bone. Despite the physical distinctions between men and women, clinical research is thin when it comes to exploring the gender distinctions in lung cancer patients.10,11 In a 2006 issue of JAMA, researchers reported that women appear to be more susceptible than men to the carcinogens present in tobacco smoke, but also have increased survival rates after diagnosis than men.12 In a 2007 publication of Lung Cancer that looks at the issue of women and lung cancer, the authors concluded that a) lung cancer development in both smokers and nonsmokers was tied to female sex and to genetic susceptibility; b) exposure to tobacco smoke and gender had an impact on lung cancer tumor histology and biology; and c) some therapies may have better effectiveness in women compared to men.1

Conclusion

Women have several distinctions due to physiology and smoking habits that have placed them at greater risk for developing lung cancer and have shown higher actual rates for getting lung cancer. Differences between the sexes in hormonal makeup, genetic make-up, and metabolism appear to have a bearing on the development of lung cancer. Research needs to distinguish between the sexes, and treatment options need to be evaluated with gender in mind. Placing restrictions and constraints on advertising aimed at young women may help curb smoking in this marketing segment. Education needs to be offered to elementary and middle school students to discourage both sexes from starting smoking. Smoking cessation strategies need to be designed with a particular focus on young women to increase success rates in this population. There are many targets to aim at when dealing with the issues of females and smoking and with the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer in women. This is a secret, silent killer that needs to be stopped in its pursuit of female victims. The more we know and understand lung cancer, the better we will be able to change the picture of women’s health.

William C. Pruitt, MBA, RRT, CPFT, AE-C, is a senior instructor in the Department of Cardiorespiratory Sciences, University of South Alabama, and is a PRN therapist at Springhill Medical Center and the Mobile Infirmary Medical Center, Mobile, Ala. For further information, contact .

References

- Belani CP, Marts S, Schiller J, Socinski MA. Women and lung cancer: epidemiology, tumor biology, and emerging trends in clinical research. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:15-23.

- Ahmedin J, Ram C, Tiwari TM, et al. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:8-29.

- Virginia Slims. Available at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_Slims. Accessed August 4, 2007.

- Thomas L, Doyle LA, Edelman MJ. Lung cancer in women: emerging differences in epidemiology, biology, and therapy. Chest. 2005;12:370-81.

- Frankly Speaking About Lung Cancer Alliance. Available at: [removed]www.lungcanceralliance.org/frankly/[/removed]. Accessed August 8, 2007.

- Cancer of the lung. In: Des Jardins T, Burton G, eds. Clinical Manifestations and Assessment of Respiratory Disease. 5th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2005:354-67.

- Malhorta A, Schwartz D. Lung cancer. In: Hess D, McIntyre N, Mishoe S, Galvin WF, Adams AB, Saposnick AB, eds. Respiratory Care: Principles and Practices. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 2002:1151-72.

- Hamilton W, Sharp D. Diagnosis of lung cancer in primary care: a structured review. Fam Pract. 2004;21:605-11.

- Patel J. Lung cancer in women. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3212-

- Du W, Gadgeel,S, Simon M. Predictors of enrollment in lung cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2006;1062:420-5.

- Murthy V, Krumholz H, Gross C. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291:2720-6.

- Henschke C, Yip R, Miettinen O. Women’s susceptibility to tobacco carcinogens and survival after diagnosis of lung cancer. JAMA. 2006;296:180-4.